Buster's War

Sunday, July 17, 2016

Showing off their Guns.

Hunting trip

Photos from Buster's Collection.

Buster took a number of photos during his time serving with the 815th Engineers in WWII using a camera he bought in England. He developed many of the photo's himself, so the quality is not that great. Some of the photos are actually the size of the negative as shown above. I will share as many as I can. I hope that you can find your relative in these images. I also hope you have photographs that your grandfather and/or great grandfather made while serving that you can share too.

I do not know the men in these images, however we know they served in the 815th Co. B or an attached unit.

Working. Building Runways for the 815th Engineers.

Do you think these images are taken in North Africa or Italy?

Buster was a mechanic for the 815th Engineers. Before the war he lived for a while with his older sister Nettie and her husband who was a mechanic. In the 1940 census, Buster is listed as a mechanic assistant in Wilcox County Alabama. As a side note, he is also listed in the 1940 census living with his Julie and sister Minnie in Clarke County. The census listing was compiled a couple months a part.

Ten Mile Hike 815th WWII

Photos of Company B 815th WWII

The back of the top photo said Ten Mile hike.

Is your grandfather in these photos?

Tuesday, July 1, 2014

Collier's Magazine December 18, 1943

Monday, July 2, 2012

Robert McCormick writing about Engineers building runways in North Africa.

Monday, June 18, 2012

Gran in Mobile

Monday, August 23, 2010

Thursday, August 19, 2010

Tuesday, July 6, 2010

1974 Reunion

Wednesday, August 19, 2009

Sheet # 82 War Diary 815th Engr. Avn. Bn. March 1945

Thursday, July 16, 2009

Detached Service

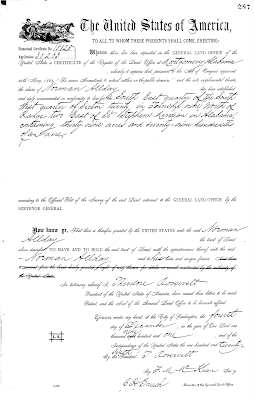

Click to enlarge document.

Click to enlarge document.This evening I found Buster's name on set of orders for detached service in the 815th's WWII war records/diary.

Regards,

Dick Bowman

(I remember Grandpa speaking of Page, the last man on the list.)

Somewhere there is a picture with Page written on the back.

Names listed...

Sgt. Louis A. Cappellano

T/5 Norman. T. Allday

T/5 Harold E. Woodside

T/5 Junior D. Page

Friday, July 10, 2009

More info on the 815th in WWII.

Read full report here. http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/AAF/VII/AAF-VII-9.html

(The information below is copy and pasted from the Army Air Forces in WWII site and is the property of the site listed above. I am copy and pasting the information for future record in case the site no longer exist. )

The 815th had lost most of its key equipment at sea, when the ship carrying it had been sunk. The 809th equipment was on a ship that had developed engine trouble two days out of England and had turned back! The 817th had no such hard luck and got to work on La Senia Airport fairly promptly, but difficulties in unloading and successfully claiming its property made the operation a memorable example of confusion the officers were determined to avoid in the future. The brightest spot in the picture was that sufficient pierced-steel landing mat had been provided to help defeat the African weather.28

In Morocco the aviation engineers were able to improve and utilize existing airstrips readily enough and to begin construction on a large all-weather base near Casablanca. But at Oran and Algiers, which were nearer the front and accordingly more crucial, heavy rains had created an almost desperate situation. Near each of those cities was an air base with hard-surfaced runways, but they could scarcely be used because aircraft had to park on the strips in preference to sinking and sticking in the adjacent mud. Aside from offering a concentrated target to the enemy, this situation virtually held up the Allied air war. On 2 December 1942 General Davison flew to the village of Talergma, located on a high, flat plateau between the Saharan and the Maritime Atlas Mountains near the Tunisian boundary, where the French had informed him dry weather usually prevailed. Davison walked about until he had satisfied himself the soil combination was good. Later in the day a party of aviation engineers moved in from the coast and with the assistance of Arabs began at once to clear the first of several airstrips. Other troops of the 809th EAB soon came in by air and truck, and by 13 December a B-26 landed smoothly on the packed runway. The completion of other strips relieved congestion at Oran and Algiers by allowing the removal of the medium bombers and most of the fighters to the Talergma area.29

Advanced details of three aviation engineer battalions (the 809th, 814th, and 815th) were to land on D Day and repair captured airfields or carve out new ones as necessary. Until the sailing, all the men could do was work on their equipment, which most of them liked to do, and undergo training in the art of staying alive in combat, which most of them bitterly resented, even though the North African experience had indicated they were far from expert in such matters.44

On D Day, 10 July 1943, a small detachment of the 814th Engineers,

( Jenni here... Is this date correct?)

attached temporarily to the 19th Engineer Combat Regiment, dragged their equipment from the landing craft to the beaches and proceeded inland to a large captured airdrome at Comiso. It took only a little time to repair the craters in its runway, partly because the Germans had left an asphalt plant behind. Next the men of the 814th EAB groped their way to Biscari, putting its field back into operation within four days, the worst aspect of the task being the burial of the enemy dead found there. The twelve aviation engineers of the 809th EAB, who landed with the 1st Division at Gela, were less successful. Some equipment was lost, and a paneled emergency airstrip prepared on D Day was overrun by the Germans on the next day. Moving on 12 July to the former main enemy base at Ponte Olivo, which was said to be cleared, the engineers found it intricately mined and under artillery fire. The painstaking work of removing the mines and filling the small craters took all night; by 13 July, however, the field was operational and out of the enemy’s artillery range. A field near the landing beach, later known as Gela East, had been crisscrossed by barbed wire. Three hours after the handful of engineers with the aid of prisoners of war started to clear it, a damaged Fortress was able to land. Soon the airdrome was ready for emergency use on larger scale, although the troops lacked fuel, oil, equipment, and, much of the time, rations and water. The arrival of the 809th EAB and its machinery made it possible to finish the rehabilitation of Ponte Olivo and Gela East and to begin a dry-weather field at Gela West within a few days. During this phase of the invasion, the aviation engineers had been subjected to German shells, strafings, and the devilish thermal bombs scattered at night, all of which caused casualties but scarcely held up the work of reconstruction.45

On the westernmost American beach, at Licata, a company of the 815th EAB landed despite dive bombers and strafing German planes and sent a survey party to examine an airfield the Allies hoped to rehabilitate. The engineer in charge decided it would be simpler to construct a new runway, and this the troops did within two days, although most of their heavy equipment was still on the beaches. Allied aircraft descended on the runway in numbers and took off on tactical support missions. Since service troops had not arrived, the aviation engineers had to refuel and rearm the fighters for almost a week. Within a few days the German attacks abruptly ceased, not only at Licata, but in the whole invasion area, and the engineers, now

with their three battalions at almost full strength, had bases ready for 34 fighter squadrons on 20 July.46 For the most part the battalions were well equipped and had managed to retain contact with their equipment. Hectic as the first few days on Sicily were, the aviation engineers had performed very creditably.

Some of the 815th engineers accompanied the Third Division as it crossed Sicily from south to north, a journey which taxed the skill and patience of the men in moving their heavy machinery along the treacherous mountain roads of the island. Once on the northern side, the 815th cleared in a few hours a captured airdrome near Palermo and scratched out bases for fighters and transports east of the city. The withdrawal of the Germans indicated that the battle for Sicily was won. The aviation engineers had done what they were supposed to do. Even the weather had been good, a circumstance so rare when things went badly, so unremarked when they went well. For the next few weeks the aviation engineers worked on barracks, water points, electric power systems, and other necessities that were only frills during combat phases of an operation. Soon the 809th and 814th were preparing thirteen fields, mostly dry-weather, to support projected troop-carrier operations. These fields were scattered over Sicily, and the engineering problems varied with the locality, but none proved formidable. All the bases were ready a day or two before the completion date, 31 August.47

The next operation—the invasion of Italy—was already under way. For the crucial landing at Salerno the short range of the Spitfires posed a problem. The British fighters would be indispensable for protection of the invasion beaches, and the only area in Sicily close enough to Salerno was a small strip of coastal plain on the Milazzo peninsula. The mountains crowded the plain so closely that airfields would have to be laid out end to end with two miles in between, and other safety factors would have to be disregarded. That was the way it had to be if the Salerno landings were to be supported by Spitfires,

--256--

and the 815th EAB duly constructed five runways according to this plan. Much of the work was performed by Italians, whose pay probably failed to compensate for the destruction of their vineyards. Equipment left behind by the Germans was useful. The chief hazard was dust, which became such a deterrent and nuisance the aviation engineers piped water in from the sea for sprinkling and later borrowed some oil from the Royal Navy. The job was finished on time, and the fields served the Spitfires for the Salerno operation. Even the dangers posed by the proximity of the mountains did not result in the loss of a single aircraft. The only sour note in the operation was the hurried dispatch of a detachment of the 815th EAB to Catania, on the eastern side of Sicily, in reply to an urgent call for airfield and road construction. As it turned out, the airdrome was not feasible, and the engineers, pulled away from the Milazzo job, worked on a road until they were withdrawn for more important tasks in Italy. Air engineers grumbled that road construction should have been the job of the Army engineers.48

The next mission was the construction of all-weather bases in the Naples area. The able and experienced British 15th Airdrome Construction Group went to work on two permanent facilities there. Company C of the 815th EAB joined the British organization in October 1943, fresh from a two-week experiment at Cercola, near the base of Mt. Vesuvius. (Jenni again. There is a picture of this .) Clearing away ancient buildings and filling wells had been routine enough, but using fresh volcanic ash from brooding Vesuvius as a substitute material for paving runways was indeed novel. Farther away, the British and other companies of the 815th worked on all-weather bases at Marcianise and Santa Maria. Marcianise proved to be a slow job because rain fell on fifty of the seventy-three days required for building it. At Santa Maria, higher headquarters changed plans at least five times, with the result that the aviation engineers were put to work and called off repeatedly. In the end, it remained a dry-weather field.53

For the Anzio landings the 815th Engineers again built a base,

--259--

Castelvolturno, for the short-ranged Spitfires. This airdrome was located on a coastal strip near the mouth of the Volturno River, about 80 miles south of the invasion area. If mud in southern Italy had immobilized much of the heavy equipment, at least here the beach sand permitted its operation. Malaria seemed the worst threat as the 815th Engineers began work on 1 December 1943. It turned out, however, that the malignant Italian weather of that memorable winter caught up with them. Rains caused ground water to rise to a point that flooded much of the runway, but the steel mat was laid in time for the field to be used as planned for the Anzio operation. The aviation engineers by planting rye grass even hoped to conquer a future dust problem. Another site in the vicinity, Lago, was also a responsibility of the heavily taxed 815th EAB. Compared with Castelvolturno, it proved fairly simple to build.54

A complex of bases for heavy bombers and long-range fighters in the Heel of Italy and in the Foggia area was expected to have a decisive bearing on the success of the strategic air offensive, and the provision of these airdromes became first priority in the engineer command. Nearly all the steel mat in the theater was concentrated on this program, although the British finally won a few concessions for the Desert Air Force, which was to need bases up the eastern coast of Italy. As soon as the Desert Air Force moved out of the Heel, the 21st Engineer Aviation Regiment and the 809th and 385th Battalions came in to enlarge and strengthen the existing fields of Lecce, San Pancrazio, Mandura, Brindisi, Gioia, and Grottaglie, all of them for Fifteenth Air Force heavy bombers but Grottaglie, which was to be a fighter base. The deadline for this reconstruction was 31 October 1943, but the slow arrival of the aviation engineers pushed it back to 10 November, and it was actually in December before the heavies could be based in the Heel.55

The aviation engineers ran into trouble from the first, originally because of the difficulties in moving equipment on schedule, then because of unexpectedly evil weather, but ultimately because the job had been underestimated, not by the engineers themselves so much as by higher commanders who were eager to get the strategic air force over Germany by the southern route. At Lecce the silty soil was saturated by rain and the natural drainage so poor that the runway was not operational until February 1944. Manduria received bombers in December, but only because pierced-steel plank had been

--260--

laid on its existing surface, and such effort was required to maintain it that there was nothing left for further construction. The steel plank runway at Gioia disintegrated quickly under use. The aviation engineers scooped muck out and piled it as high as fifteen feet on each side of the runway. They used rock to raise the runway above the water. It was almost the same story at Brindisi and San Pancrazio. The winter of 1943–44 in the Heel was a nightmare of buckling runways, frenzied repairs, mud, water—and neglect of other construction. In one sense, at least, it was fortunate that the slower tempo of heavy bomber operations at that time kept the air-base situation from being more critical than it was.

The Foggia job had also appeared deceptively simple. There, a fairly level plain with a flat spread of sand and clay and abundant rock quarries seemed to offer an opportunity for rapid airfield development. The new construction involved eight airdromes. The first, Foggia Main, went off well enough. Units of the 21st Regiment and the 814th and 845th Battalions had one runway, with steel plank on a compacted fill of caliche, ready by 1 December and another by the last of January. Drainage proved good in spite of the volume of rainfall. To the east of Foggia Main, at Foggia #2, the aviation engineers laid steel plank directly on an old sod field, a measure that sometimes worked, but in this case it proved necessary to raise the mat thirteen times during the next few months and to smooth out the runway. The airdromes, known as Giulia, San Giovanni, and Toretto had high water tables and poor natural drainage. The engineers finally had to cut a deep runway and leave it open until the weather straightened out before laying gravel, compacting, and placing the steel mat. At the other fields, Foggia #1, Foggia #2, and Foggia #7, the situation was similar—a long effort to secure minimum drainage, the rather timorous laying of steel mat, and the repeated repairs and refills. Every frustration dogged the aviation engineers in their efforts toward continuous maintenance. Yet the Foggia runways were at least usable by January 1944, even if other construction lagged three months behind schedule. Naturally, living conditions for the overworked engineer troops were dismal, for they could build little for their own comfort until the all-weather bases were completed.56

In western Italy a lull developed for the first months of 1944. Thirty men of the 815th EAB went with British construction units to the Anzio beachhead, but the rest of the battalion departed for the

--261--

rear, hoping for a rest after such a long stint of airfield development. Instead, they built camp facilities for MAAF personnel and, later, quarters for general officers in the royal gardens at Caserta. When Vesuvius erupted and fallen ash had immobilized eighty-two B-25's, the aviation engineers cleared a road so that the stricken Mitchells could be taxied away. Many other jobs came their way—hauling gravel, improving all sorts of facilities, expanding and developing existing airdromes.57 Perhaps they were luckier than they realized. In other theaters aviation engineers were often employed on construction jobs that had no relation to air force needs and frequently worked longer hours under worse conditions.

The Allied offensive of May–August 1944 into northern Italy brought back the 815th, 817th, and 835th Battalions to more urgent activities. The 815th built a dry-weather field in the former Anzio beachhead, this time finding enough oil to hold the dust down, and rehabilitated a captured air base after removing several hundred Teller mines the Germans had left behind for their benefit. Following the ground forces they moved into Rome and readied three airfields, where most of the labor was a matter of removing booby traps and mines. They had only six hours to get Roma Littoria in readiness to receive transports coming in to evacuate the wounded, but that was time enough. Then the 815th continued northward, repairing cratered runways and doing whatever had to be done to make captured airdromes suitable for Allied planes. Since German air opposition was so light, Allied fighters could be used more and more for bombing and strafing. This called for lengthening airdromes from time to time, but this was not formidable work for experienced aviation engineers. Their chief concern these days was German artillery, which often remained in the vicinity of the airfields that needed repair. As noted, the 835th Battalion was concerned in these operations, having finished its hard, wet winter in the Heel, as was the 817th, which interrupted its work in Corsica for the renewed Italian offensive.58

Summary of Rpt., 815th EAB on Sicilian Operation, Avn. Engr. Notes, Apr. 1944, pp. 2–6.The problem of constructing air bases on Corsica proved extremely vexatious, if ultimately rewarding. The tactical air forces required bases there for operations against Italy and, eventually, southern France. Only four captured airfields were available for development, and all of them were inadequate for American aircraft. And other airdromes would need to be built, despite the mountainous character of the island. Fortunately, many Frenchmen and Italian prisoners

--262--

could be utilized as a labor force, and two companies of French aviation engineers were on hand. Dry-weather fields for transports and fighters were constructed and even some for medium bombers. These last, of course, received hard-surfacing and steel mat, as materials and effort became available.59 Less labor was required for the Axis airfields on Sardinia, where most of them needed little but mine removal. But the construction of a medium-bomber base at Decimomannu included the novelty of widening the runway to more than a thousand feet to permit six B-26's to take off simultaneously.60

The first aviation engineer unit to reach Corsica had an unusual history. This 812th Engineer Aviation Battalion, a Negro organization, had shipped out from Charleston, South Carolina, in May 1942 to build bases in south-central Africa on the substitute ferry route.* They put in at Freetown, Sierra Leone, had leave in the Union of South Africa, and finally arrived at Mombasa, Kenya, where they took a train into the interior. Apparently the men were much amused by the sight of giraffes loping and monkeys cavorting beside the rickety railroad. Once they had erected a tent camp in the tall grass of Kenya, where they had planned to work with the Royal Engineers on an airfield, they actually completed all they were destined to do in that area. Suddenly they were on their way back to the coast and found themselves on ships bound for Egypt. After some days of sight-seeing there, they piled into trucks and bumped for 900 miles or so across the desert to Benghazi, where for a time they were the only American engineers. There they stabilized a base for Ninth Air Force B-24's that bombed Ploesti and built a pipeline from the sea to keep the airfield sprinkled, After hauling sand and picking up rocks for an interval, the unit sailed for Sicily toward the last of 1943, and then to Corsica in January 1944. For six months they worked around the clock on airfield development, after which followed ten months of comparative leisure on the picturesque island.61 If the itinerary of the 812th Engineers was unusually colorful, the spurts of hard labor, the long waits, the sudden changes, and the enjoyment of opportunities available were typical of the wartime life of aviation engineers.

Very elaborate planning for aviation engineer operations preceded the invasion of southern France. Since a slow and difficult campaign was expected, with the autumn rains beginning at an awkward stage, the AAF Engineer Command (MTO) developed unusually detailed

Thursday, July 9, 2009

B Company of the 815th

Saturday, November 15, 2008

Happy Birthday

Monday, May 26, 2008

Just a few years ago...

Sunday, May 25, 2008

Memorial Day

Friday, April 18, 2008

Buster's Granddad

Thursday, April 17, 2008

Homestead

Saturday, March 29, 2008

Blog Link...

The Allday Glimpse.

Car at Camp

Saturday, February 16, 2008

34166518

Information found here on the Army Serial Number

| ARMY SERIAL NUMBER | 34166518 | 34166518 | ||||||||||||||

| NAME | ALLDAY#NORMAN#T | ALLDAY#NORMAN#T | ||||||||||||||

| DATE OF ENLISTMENT DAY | 23 | 23 | ||||||||||||||

| DATE OF ENLISTMENT MONTH | 01 | 01 | ||||||||||||||

| DATE OF ENLISTMENT YEAR | 42 | 42 | ||||||||||||||

| GRADE: ALPHA DESIGNATION | PVT# | Private | ||||||||||||||

| GRADE: CODE | 8 | Private | ||||||||||||||

| BRANCH: ALPHA DESIGNATION | BI# | Branch Immaterial - Warrant Officers, USA | ||||||||||||||

| BRANCH: CODE | 00 | Branch Immaterial - Warrant Officers, USA | ||||||||||||||

| FIELD USE AS DESIRED | # | # | ||||||||||||||

| TERM OF ENLISTMENT | 5 | Enlistment for the duration of the War or other emergency, plus six months, subject to the discretion of the President or otherwise according to law | ||||||||||||||

| LONGEVITY | ### | ### | ||||||||||||||

| SOURCE OF ARMY PERSONNEL | 0 | Civil Life | ||||||||||||||

| NATIVITY | 41 | ALABAMA | ||||||||||||||

| YEAR OF BIRTH | 16 | 16 | ||||||||||||||

| RACE AND CITIZENSHIP | 1 | White, citizen | ||||||||||||||

| EDUCATION | 0 | Grammar school | ||||||||||||||

| CIVILIAN OCCUPATION | 983 | Unskilled mechanics and repairmen, n.e.c. | ||||||||||||||

| MARITAL STATUS | 6 | Single, without dependents | ||||||||||||||

| COMPONENT OF THE ARMY | 7 | Selectees (Enlisted Men) | ||||||||||||||

| CARD NUMBER | # | # | ||||||||||||||

| BOX NUMBER | 0762 | 0762 | ||||||||||||||

| FILM REEL NUMBER | 1.279 | 1.279 |

Louis A. Cappellano was from Queens, NY.

Junior D. Page was from Kern CO. California via Oklahoma

Harold E. Woodside was from San Bernardino, CA